The Truth About Marijuana

Legal doesn’t mean right. Illegal doesn't mean wrong.

Before the prohibition of hemp with the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, there was great application potential for all hemp/cannabis related products.

Laws like this one are normally created to aid political/financial agenda and not for the “greater good”.

American Medical Association Opposes the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937

Since the medicinal use of cannabis has not caused and is not causing addiction, the prevention of the use of the drug for medicinal purposes can accomplish no good end whatsoever. How far it may serve to deprive the public of the benefits of a drug that on further research may prove to be of substantial value, it is impossible to foresee.

The American Medical Association has no objection to any reasonable regulation of the medicinal use of cannabis and its preparations and derivatives. It does protest, however, against being called upon to pay a special tax, to use special order forms in order to procure the drug, to keep special records concerning its professional use and to make special returns to the Treasury Department officials, as a condition precedent to the use of cannabis in the practice of medicine. in the several States, all separate and apart from the taxes, order forms, records, and reports required under the Harrison Narcotics Act with reference to opium and coca leaves and their preparations and derivatives.

If the medicinal use of cannabis calls for Federal legal regulation further than the legal regulation that now exists, the drug can without difficulty be covered under the provisions of the Harrison Narcotics Act by a suitable amendment. By such a procedure the professional use of cannabis may readily be controlled as effectively as are the professional uses of opium and coca leaves, with less interference with professional practice and less cost and labor on the part of the Treasury Department.

It has been suggested that the inclusion of cannabis into the Harrison Narcotics Act would jeopardize the constitutionality of that act, but that suggestion has been supported by no specific statements of its legal basis or citations of legal authorities.

Wm. C. Woodward,

Legislative Counsel

[Whereupon at 11:37 AM Monday, July 12, 1937, the subcommittee adjourned.] See Full Post

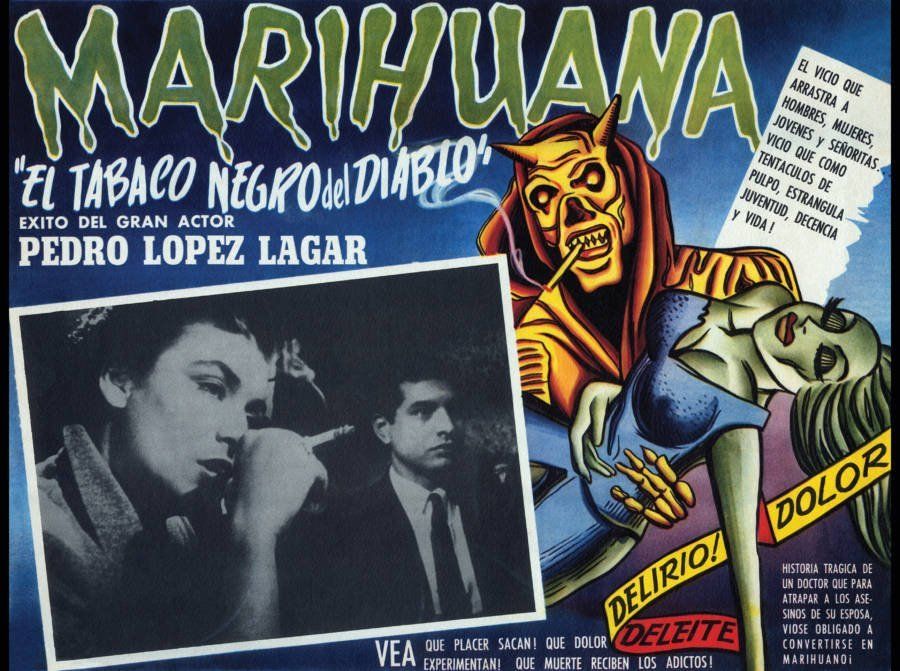

ANTI-HEMP PROPAGANDA IN THE 1930'S

Crazy orgies, conversations with Satan, permanent insanity, and murder: These were the calamities that could befall marijuana users of the early 20th century — according to anti-marijuana propaganda.

And this anti-reefer hysteria was, at least in part, the product of belligerent Federal Bureau of Narcotics Commissioner Harry J. Anslinger's 1930 one-man "call to arms" campaign against the drug, and others.

To support his claims, he solicited and received a number of dubious anecdotal accounts of marijuana-induced violence. He recounted tales like that of Victor Licata, who allegedly murdered his family with an ax while high on cannabis — though it later emerged that he was mentally ill and had no history of drug abuse.

That didn't stop Harry Anslinger — and neither did the medical community. When 29 out of 30 doctors and pharmacists he contacted told him that the drug posed no serious danger to the public, he went with the single professional who disagreed.

At the time, marijuana use wasn't widespread — but on the radio and on talk shows, Anslinger described an epidemic. He said it was a "shortcut to the insane asylum" and could make "a murderer who kills for the love of killing out of the mildest mannered man."

His anti-marijuana propaganda had strong racial undertones. He persecuted jazz musicians, saying that weed was leading them to make the devil's music. Under his influence, the term "cannabis" was replaced with the Spanish word "marijuana" — a shift he used to link the drug and its usage to Latinos.

Thanks to his strategic use of mass media and emotionally jarring headlines steeped in racism, anti-marijuana propaganda spread from sea to shining sea, uniting an otherwise struggling and divided nation in a fight against the drug.

The anti-marijuana fervor only escalated throughout the latter half of the 20th century, and since Richard Nixon formally declared a war on drugs in 1971, the US government has spent around $1 trillion fighting — however nominally — the illegal drug trade.

While Attorney General Eric Holder came out against

this failed endeavor in 2013 and marijuana laws

have grown more and more lax, it's going to take a lot more than a few amendments to change a culture so fixated on the terror of a single plant.

- The New York Times newspaper headline "State Finds Many Children are Addicted to Weed."

- "Reefer makes darkies think they’re as good as white men." Harry J. Anslinger, U.S. Narcotics Commissioner.

- The 1936 film, "Reefer Madness" by Louis J. Gasnier portrays a man killing his entire family with an ax after smoking Marijuana.

- Newspaper headline "Marijuana: The Devil's Weed with Roots in Hell."

THE COTTON INDUSTRY WANTED TO REPLACE HEMP

For the first 162 years of U.S. history, Hemp was a common crop known by all Americans for its many industrial purposes. In the 1930s, new industries such as Cotton, Synthetic Plastics, Liquor, and Timber became able to replace Hemp. Conspiracy Theorists believe these industries funded misinformation campaigns to make a way for these new technologies to replace Hemp.

THE INFLUENCE OF HENRY J. ANSLINGER

California's 1913 narcotics law banned possession of cannabis preparations -- which California NORML head Dale Gieringer believes was a legal error, that the provision was intended to parallel those affecting opium, morphine and cocaine. The law was amended in 1915 to ban the sale of cannabis without a prescription. "Thus hemp pharmaceuticals remained technically legal to sell, but not possess, on prescription!" Gieringer wrote in The Origins of Cannabis Prohibition in California. "There are no grounds to believe that this prohibition was ever enforced, as hemp drugs continued to be prescribed in California for years to come." In 1928, the state began requiring hemp farmers to notify law enforcement about their crops.

New York City made cannabis prescription-only in 1914, part to pre-empt users of over-the-counter opium, morphine and cocaine medicines from switching to cannabis preparations, but with allusions to hashish use by Middle Eastern immigrants. In the West and Southwest, anti-Mexican sentiment quickly came into play. California's first marijuana arrests came in a Mexican neighborhood in Los Angeles in 1914, according to Gieringer, and the Los Angeles Times said "sinister legends of murder, suicide and disaster" surrounded the drug. The city of El Paso, Texas, outlawed reefer in 1915, two years after a Mexican thug, "allegedly crazed by habitual marijuana use," killed a cop. By the time Prohibition was repealed in 1933, 30 states had some form of pot law.

The campaign against cannabis heated up after Repeal. "I wish I could show you what a small marihuana cigaret can do to one of our degenerate Spanish-speaking residents," a Colorado newspaper editor wrote in 1936. "The fatal marihuana cigarette must be recognized as a DEADLY DRUG, and American children must be PROTECTED AGAINST IT," the Hearst newspapers editorialized.

Harry Anslinger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, headed the charge. "If the hideous monster Frankenstein came face to face with the monster marihuana, he would drop dead of fright," he thundered in 1937.

An ambitious racist (a 1934 memo described an informant as a "ginger-colored nigger") who had previously been federal assistant Prohibition commissioner, Anslinger railed against reefer in magazine articles like 1937's "Marihuana: Assassin of Youth." It featured gory stories like that of Victor Licata, a once "sane, rather quiet young man" from Tampa, Fla., who'd killed his family with an axe in 1933, after becoming "pitifully crazed" from smoking "muggles." (Actually, the Tampa police had tried to have Licata committed to a mental hospital before he started smoking pot.)

Anslinger strongly opposed Hemp. Read his 1937 testimony before Congress below:

"Marijuana is the most violence-causing drug in the history of mankind. Most Marijuana smokers are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz, and swing, result from marijuana usage. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes."

Anslinger's other theme was that white girls would be ruined once they'd experienced the lurid pleasures of having a black man's joint in their mouth. "Colored students at the Univ. of Minn. partying with female students (white) smoking and getting their sympathy with stories of racial persecution," he noted. "Result, pregnancy."

In 1937, after a very cursory debate, Congress enacted the Marihuana Tax Act, levying a prohibitive $100-an-ounce tax on cannabis. "I believe in some cases one cigarette might develop a homicidal mania," Anslinger testified in a hearing on the bill.

Corporate Interests

Making matters worse, Harry Anslinger, who in the 1930s was the first appointee as commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, upheld W.R. Hearst’s exaggerated claims about the deleterious nature of cannabis. Anslinger was responsible for introducing the Marijauna(Marijuana) Tax Act to Congress, beginning the legal process that answers the question, “Why was hemp outlawed?”

In the 1920's the Du Pont company developed and patented fuel additives such as tetraethyl lead, as well as the sulfate and sulfite processes for manufacture of pulp paper and numerous new synthetic products such as nylon, cellophane, and other plastics. At the same time other companies were developing synthetic products from renewable biomass resources--especially hemp. The hemp decorticator promised to eliminate much of the need for wood-pulp paper, thus threatening to drastically reduce the value of the vast timberlands still owned by Hearst. Ford and other companies were already promising to make every product from cannabis carbohydrates that was currently currently being made from petroleum hydrocarbons. In response, from 1935 to 1937, Du Pont lobbied the chief counsel of the Treasury Department, Herman Oliphant, for the prohibition of cannabis, assuring him that Du Pont's synthetic petrochemicals (such as urethane) could replace hemp seed oil in the marketplace.

William Randolf Hearst hated minorities, and he used his chain of newspapers to aggravate racial tensions at every opportunity. Hearst especially hated Mexicans. Hearst papers portrayed Mexicans as lazy, degenerate, and violent, and as marijuana smokers and job stealers. The real motive behind this prejudice may well have been that Hearst had lost 800,000 acres of prime timberland to the rebel Pancho Villa, suggesting that Hearst's racism was fueled by Mexican threat to his empire.

Marijuana is actually less dangerous than alcohol, cigarettes, and even most over-the-counter medicines or prescriptions. According to Francis J. Young, the DEA's administrative judge, "nearly all medicines have toxicm, potentially letal affects, but marijuana is not such a substance...Marijuana, in its natural form, is one of the safest therapeutically active substances known to man. By any measure of rational analysis marijuana can be safely used within a supervised routine of medical care" ( DEA Docket No. 86-22, 57 ). It is illogical then, for marijuana to be illegal in the United States when "alcohol poisoning is a significant cause of death in this country" and "approximately 400,000 premature deaths are attributed to cigarettes annually." Dr. Roger Pertwee, Secretary of the International Cannabis Research Society states that as a recreational drug, "Marijuana compares favourably to nicotine, alcohol, and even caffeine." Under extreme amounts of alcohol a person will experience an "inability to stand or walk without help, stupor and near unconsciousness, lack of comprehension of what is seen or heard, shock, and breathing and heartbeat may stop." Even though these effects occur only under insane amounts of alcohol consumption, (.2-.5 BAL) the fact is smoking extreme amounts of marijuana will do nothing more than put you to sleep, whereas drinking excessive amounts of alcohol will kill you.The most profound activist for marijuana's use as a medicine is Dr. Lester Grinspoon, author of Marihuana: The Forbidden Medicine. According to Grinspoon, "The only well-confirmed negative effect of marijuana is caused by the smoke, which contains three times more tars and five times more carbon monoxide than tobacco. But even the heaviest marijuana smokers rarely use as much as an average tobacco smoker. And, of course, many prefer to eat it." His book includes personal accounts of how prescribed marijuana alleviated epilepsy, weight loss of aids, nausea of chemotherapy, menstrual pains, and the severe effects of multiple sclerosis. The illness with the most documentation and harmony among doctors which marijuana has successfully treated is MS. Grinspoon believes for MS sufferers, "Cannabis is the drug of necessity." One patient of his, 51 year old Elizabeth MacRory, says "It has completely changed my life...It has helped with muscle spasms, allowed me to sleep properly, and helped control my bladder." Marijuana also proved to be effective in the treatment of glaucoma because its use lwoers pressure on the eye.

Prohibition's Racist History

The belief that marijuana prohibition came about because of the secret machinations of an economic cabal ignores the pattern of every drug-law crusade in American history. From the 19th-century campaigns against opium and alcohol to the crack panic of the 1980s, they have all been fueled by racism and cultural war, conflated with fear of crime and occasionally abetted by well-intentioned reform impulses. (The financial self-interest of the prison-industrial complex has been a more recent development.) The first drug-prohibition laws in the United States were opium bans aimed at Chinese immigrants. San Francisco outlawed opium in 1875, and the state of California followed six years later. In 1886, an Oregon judge ruled that the state's opium prohibition was constitutional even if it proceeded "more from a desire to vex and annoy the 'Heathen Chinee'… than to protect the people from the evil habit," notes Doris Marie Provine in Unequal Under Law: Race in the War on Drugs. In How the Other Half Lives

, journalist Jacob Riis wrote of opium-addicted white prostitutes seduced by the "cruel cunning" of Chinese men.

The path to the 1914 federal narcotics law that limited cocaine and opioids to medical use -- and was almost immediately interpreted as prescribing narcotics to addicts -- was more complex. The main rationale was ending the over-the-counter sale of patent medicines such as heroin cough syrup, but there was a definite racist streak among advocates for controlling cocaine. "Cocaine is often the direct incentive to the crime of rape by the Negroes," Hamilton Wright, the hard-drinking doctor-turned-diplomat who spearheaded the first major multinational drug-control agreements, told Congress. In 1914, Dr. Edward Huntington Williams opined in the New York Times Magazine

that "once the negro has formed the habit, he is irreclaimable. The only method to keep him from taking the drug is by imprisoning him."

The movement to prohibit alcohol was part puritanical, part racist. In the big cities, it was anti-immigrant. Bishop James Cannon of the Anti-Saloon League in 1928 denounced Italians, Poles and Russian Jews as "the kind of dirty people that you find today on the sidewalks of New York," while in 1923, Imogen Oakley of the General Federation of Women's Clubs described the Irish, Germans, and others as "insoluble lumps of unassimilated and unassimilable peoples … 'wet' by heredity and habit." In the South, it was anti-black. "The disenfranchisement of Negroes is the heart of the movement in Georgia and throughout the South for the Prohibition of the liquor traffic," Georgia prohibitionist A.J. McKelway wrote in 1907. "Liquor will actually make a brute out of a negro, causing him to commit unnatural crimes," Alabama Rep. Richmond P. Hobson told Congress in 1914, a year after he'd sponsored the first federal Prohibition bill. (He said it had the same effect on white men, but took longer because they were "further evolved.")

Prohibitionism was an early example of fundamentalist Christians' political strength. The midpoint of William Jennings Bryan's odyssey from the prairie populist of 1896 to the evolution foe of 1925 was his endorsement of Prohibition in 1910. The rural puritans were abetted by middle-class do-gooders who, when they saw a slum-dwelling factory hand come home drunk and beat his wife, would blame the saloon instead of the pressures of capitalist exploitation or the license of misogyny. And many industrial employers, including DuPont's gunpowder division, demanded abstinent workers. World War I's austerity was the final piece of the puzzle.

Prohibitionists played key roles in the campaign to outlaw cannabis. Harry Anslinger had been so hardline that he advocated prosecuting individual users for possession of alcohol. (Federal Prohibition, unlike the current marijuana laws, only banned sales, allowed personal possession and limited home brewing, and had an exemption for medical use.) Richmond P. Hobson, who crusaded against drugs in the 1920s as head of the World Narcotic Defense Association, was an early advocate of marijuana prohibition. In 1931, he told the federal Wickersham Commission that marijuana used in excess "motivates the most atrocious acts." And in early 1936, the General Federation of Women's Clubs joined Anslinger's campaign to make reefers verboten.

In a country that was puritanical and racist enough in 1919 to outlaw alcohol in 1919, forbidding cannabis was politically very easy. Alcohol had been the most pervasive recreational drug in the Western world for millennia. Marijuana was virtually unknown. And though Prohibitionists -- like the immigration laws of the 1920s, the resurgent Ku Klux Klan, and the 1928 presidential campaign against Irish Catholic Democrat Al Smith -- demonized whiskey-sodden Micks, wine-soaked wops, traitorous beer-swilling Krauts and liquor-selling Jew shopkeepers, at least those people were sort of white. Marijuana was used mainly by Mexican immigrants and African-Americans.

The Nixon-era escalation of the war on drugs was one of the few times in U.S. history when white users were a prime target, as marijuana and LSD provided legal pretexts to attack the '60s counterculture. Richard Nixon's White House tapes captured him in 1971 growling that "every one of the bastards that are out for legalizing marijuana is Jewish." But Nixon and other law-and-order politicians were most successful when they lumped youthful cultural-political rebellion and black militance with ghetto heroin addiction and the rising crime of the 1970s. New York's draconian Rockefeller drug laws, passed in 1973 as Gov. Nelson Rockefeller was trying to look "tough on crime," were a harbinger of the federal mandatory minimums of the 1980s. The result was that more than 90 percent of the state's drug prisoners are black or Latino.

The crack hysteria of the late 1980s was another example of the fear of dark-skinned demons breeding racially repressive law enforcement. Both federal and many state crack laws were designed to snare street dealers and bottom-level distributors, giving them the same penalties as powder-cocaine wholesalers. The racial results were obvious almost immediately. In overwhelmingly white Minnesota, more than 90 percent of the people convicted of possession of crack in 1988-89 were black. In the early 1990s, the U.S. Attorney's office in Southern California went more than five years without prosecuting a white person for crack.

That pattern still holds: In 2003, 81 percent of the defendants sentenced on crack charges nationwide were black. And law enforcement didn't spare the African-American innocent. In an August 1988 drug raid on an apartment block on Dalton Avenue in South Central Los Angeles, 88 city cops smashed walls and furniture with sledgehammers and axes, beat people with flashlights, and poured bleach on residents' clothes -- and arrested two teenagers who didn't live there on minor drug charges.

Remember it is our duty as WE THE PEOPLE to research and understand the world that is being created around us through policy and laws created by the few for the few and not the majority.

Staywoke & Question Everything.

Sources - National Archives -395 U.S. 6 (more) 89 S. Ct. 1532, 23 L. Ed. 2d 57, 1969 U.S. LEXIS 3271, 69-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) ¶ 15,900, 23 A.F.T.R.2d (RIA) 2006 - US Supreme Court